Illuminating the Complexities of Reading and Relevance

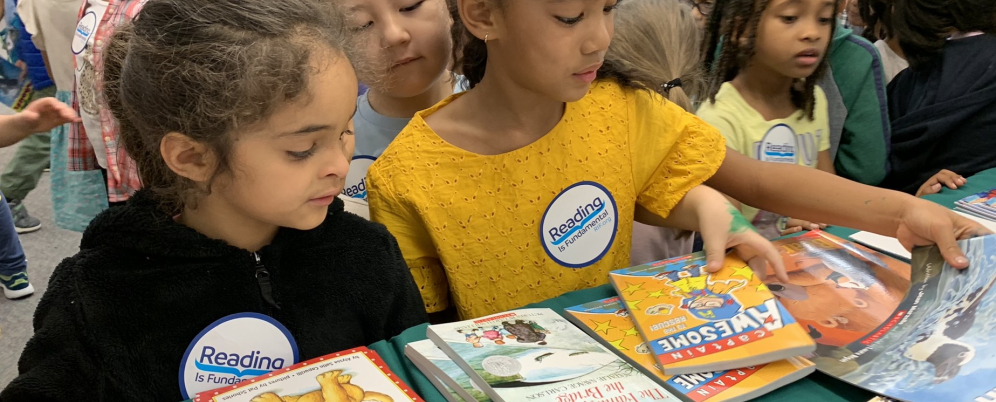

Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) believes in the transformative power of books when it comes to helping students grow into critical thinkers and lifelong learners. We are committed to supporting readers from all backgrounds by ensuring access to books that reflect their identities, experiences, interests and lives. Sometimes, though, “relevance” can be oversimplified, reduced to surface-level assumptions about students' identities and missing the deeper connections that make reading meaningful. Read on to learn how University of Georgia Assistant Professor Katie Sciurba, Ph.D., challenges this narrow view, and discover how her research highlights that relevance is deeply personal and complex, urging educators to adopt a student-centered approach that values students’ lived experiences and voices over imposed definitions of what is “relevant.”

“I love to read! I love learning about, basically, everything – everything I can get my hands on.” – Angel, 5th grade

Over the last 20 years, I have worked in education spaces, starting as an elementary school teacher and continuing through my current role as a literacy professor and teacher educator, and I have frequently used (and heard) the terms “relevance” or “relevant” in discussions about reading: “Students need books that are relevant to them,” “This text lacks relevance,” “I need to find materials that are more relevant to my kids.”

Connected (loosely or superficially) to Gloria Ladson-Billings’s (1994, 1995) signature work on culturally relevant pedagogy, which stressed the overlapping importance of “student learning,” “cultural competence,” and “sociopolitical awareness,” relevance is far too commonly put into practice in ways rooted in assumptions about who young people are, culturally or otherwise. For instance, Spanish-inclusive books might be selected and presumed most relevant for Latine students, irrespective of the story’s content. Or, book access is limited and a number of titles, therefore, cannot be, or even have a chance to become, relevant to young readers – despite children’s and teens’ actual literacy needs and interests.

Inspired by what I had witnessed with my 4th- and 5th-grade students in the Bronx– with their gravitations toward stories that reflected their families, their city context, their desires to find humor in the texts they read, and/or to read about main characters their age – I dedicated my doctoral research to talking directly with students to learn more about how “textual relevance,” as I called it, took shape. For my initial study, I engaged with a group of young men of color, including Angel, who is quoted above, to find out how they constructed meaning as readers.

The 13 young men who participated in my dissertation study, as 4th- through 8th-graders, illuminated the complexities of reading and relevance. They challenged stereotypes about boy readers by constructing relevance from books with female protagonist like the one in Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak. They stretched beyond their current New York City existences to find relevance in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, and they discussed Harry Potter’s heroic trajectory in ways that mirrored the reasons they found Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X relevant to their lives as South Asian, Latino, and/or Black young men – even if they did not “see” themselves reflected in the story.

Ten years after my initial interviews, I was able to reconnect with six of the young men – Angel, Marshall, Omari, Freddy, Franklin, and Patrick – to see how their experiences with reading and relevance had shifted as they entered adulthood. Through this work, I realized that my own conceptualization of “relevance,” as “personal meaning,” did not adequately capture the fullness of what happened when the young men connected to what they read.

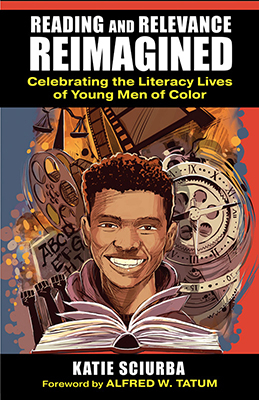

Angel, who still loved to read at age 20, noted, “The power of books is that you can project yourself into them, regardless of the situation.” He appreciated books by Junot Diaz that reflected his Dominican roots, just as much as he loved Terence McKenna, whose philosophical writings aligned with his own views about living in an expansive world. In my book, Reading and Relevance, Reimagined: Celebrating the Literacy Lives of Young Men of Color (Teachers College Press, 2024), which centers on the then-and-now reading experiences of the young men, I argue that part of the reason we, as educators and other caring adults, can so easily miss the mark in determining when, why, and how readers achieve relevance is because the term “relevance” itself has not been adequately defined.

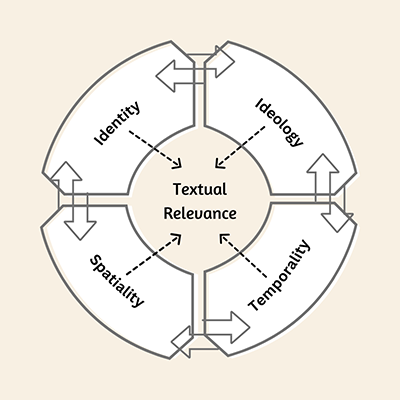

I advocate in my scholarship and in my webinar for Reading Is Fundamental (available to view in RIF’s webinar archive) for a reimagination of relevance – understood as “the condition of being practically, socially, and/or conceptually applicable to one’s life.” The following four dimensions of relevance can guide educators in supporting the reading and meaning-making experiences of students in ways that honor the complexities of their lives and enhance their criticality:

- Identity

- Spatiality

- Temporality

- Ideology

Who our students are within and beyond the bodies they inhabit; where they are from, where they have been, and the ways in which the places and spaces in which they find themselves are constructed; how old they are, how they are experiencing a particular temporal moment, and how they reflect back upon and project toward other times; and how they read, analyze, and make sense of the world all contribute to the ways in which relevance takes shape.

To effectively support young people on their journeys toward textual relevance, which ultimately empowers them to see and critique their worlds, we must take our cues from them. Rather than make guesses, based on what we see or what we think is relevant (or irrelevant) to them, our students must illuminate their own reading paths for us.

Katie Sciurba, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of Literacies and Children’s Literature in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia. Her publications have appeared in such venues as Journal of Literacy Research, Research in the Teaching of English, Teachers College Record, Journal of Children’s Literature, and Children’s Literature in Education. She is the author of the scholarly book, Reading and Relevance, Reimagined: Celebrating the Literacy Lives of Young Men of Color (Teachers College Press, 2024), and the picture book, Oye, Celia!: A Song for Celia Cruz (Henry Holt, 2007). Connect with her at katiesciurba.com.

References

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African-American children. Jossey-Bass.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491.